Yesterday I walked through a story.

Yesterday I walked through a story.

It happened by chance. I was at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, doing research, and I got lost on the way to the Canada Hall. In the process of trying to get un-lost, I came across the museum’s brand-new Empress of Ireland exhibit. A crowd had gathered outside its doors.

It looked like a tour, the kind that some museums have every hour or so. I decided to tag along. I’d heard of the Empress, but knew next to nothing about it.

The Empress of Ireland (subtitled Canada’s Titanic by the museum) collided with another ship on the St. Lawrence River in May 1914. It took less than 15 minutes for the Empress to sink into the frigid waters of the St. Lawrence. More than 1000 of the 1477 people aboard died.

The disaster gets forgotten. Although the world cared, and cared deeply, the Empress belonged to a time that was about to be swept away by World War I. And in the contemporary imagination, thanks partly to James Cameron’s movie, the Empress is left in the Titanic’s mighty wake.

The tour started in the museum’s version of Québec Harbour. There were sounds of seagulls, of people coming and going. Harbour noises. Trunks and luggage sat atop display cases. We learned about the people travelling aboard the Empress — who they were, why they were aboard, how this trip to Liverpool would carry them closer to their hopes and dreams. The man giving the tour explained that in this large, optimistically open space, the museum was trying to create a feeling of safety, of confidence. This was a routine voyage. What could go wrong?

The tour started in the museum’s version of Québec Harbour. There were sounds of seagulls, of people coming and going. Harbour noises. Trunks and luggage sat atop display cases. We learned about the people travelling aboard the Empress — who they were, why they were aboard, how this trip to Liverpool would carry them closer to their hopes and dreams. The man giving the tour explained that in this large, optimistically open space, the museum was trying to create a feeling of safety, of confidence. This was a routine voyage. What could go wrong?

As we move through the exhibit, he warned, the spaces would get darker and narrower, conveying the sense of rising tension. Communicating, maybe, the sense of the inevitable — the feeling of being unable to escape.

As we moved into the next zone of the tour, learning about the ship and her captain, I noticed that many people in the group were taking notes. More worryingly, most of them wore name tags. I tried to linger at the back. By now I was hooked — I wanted to hear what the man had to say — but I had to admit that I probably didn’t belong. Maybe it would be all right to stay on the fringes, not blocking anyone’s view. But a tour group shifts and wraps like an amoeba, front to back and back to front, and my purse is the size of a life buoy. I don’t skulk easily.

“You’re lucky,” a woman beside me said, “You managed to get in on the training session.”

“Is it all right that I’m here?”

“Of course, you’re welcome,” she said. “But you’re lucky. Most people don’t get to see this.”

Lucky. Lucky was good. Lucky was not ‘I’m about to call security and have you arrested.’ Thank you, kind lady. I smiled and took out my notepad.

The tour guide pointed out that we were moving through both space and time in the exhibit, exploring the interior of the ship and learning how passengers and crew filled the hours of the voyage. And the hours, of course, were counting down. We saw glass display cases, filled with artifacts from the time period and some from the Empress herself. Black and white photos of the ship and the people aboard were projected onto the backgrounds of the display cases. You could almost feel that you’re moving through the real ship.

It’s haunting, being met with the faces of individuals who were aboard. The photos are well chosen. There’s no reducing these people to statistics; you’ve seen them skipping rope on deck, playing cards in the lounge. Smiling, or looking worried or tired. Looking out over the water. They’re real.

The ship artifacts are real, too. You see the torn-off leg of a grand piano, water-twisted and worn to bare, gnarled wood, and in the background, you see the same piano, polished and smooth and whole, waiting for the first-class passengers to slide into the gilded lounge.

Past and present, all one.

The exhibit moves through a narrow passageway that details the timeline leading up to the collision. This part of the exhibit is more minimal. The events speak for themselves.

The passageway empties into a wider room, dark and round. A single brass ship’s bell, pulled from the wreckage, sits alone in the middle. The bell is lit so that it seems to glow. There’s little to read here, no analytics to reduce the impact. On the walls, pictures play. People falling, swimming. Going under. Artist’s renditions, put together from the stories of those who survived. The soundtrack is voices, calls for help. The room is all image and sound and emotion.

A long time ago, I read a book on cartooning. The more basic the drawn figure, it said, the more people can identify with it. Mona Lisa is one specific person, but a stick figure could be anyone. The people on the walls of the bell room are cartoons. That doesn’t diminish the impact; it increases it. They could be anyone. They’re themselves. They’re us.

After the bell room comes the aftermath. The rescue attempts. Bringing the survivors, and the dead, ashore. A small community opening up its arms to an influx of damaged, grieving people.

After the bell room comes the aftermath. The rescue attempts. Bringing the survivors, and the dead, ashore. A small community opening up its arms to an influx of damaged, grieving people.

The display space widens again, and brightens, as we move through the global reaction, the newspapers, the support efforts. The inquest. Walking through the last moments of the exhibit, we start to be able to breathe again. The immediacy of the tragedy fades; things are put into historical context.

“How did you like it?” the kind lady whispered.

“It was incredible.” It was on my tongue, the thought that had been growing in my mind. The display had moved me, so of course I’d had my knee-jerk writerly reaction. “I write books for children. I want to write about this.” A story and a character had been bumping at the edges of my brain since not long after Québec Harbour.

“Hmm,” she said. “I think someone already has.”

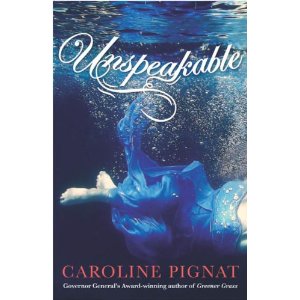

A few moments later, the tour guide confirmed it. “Our own Caroline Pignat has just published a book on the subject. We’re hoping to have an event here later in the summer.”

Had I been feeling slightly less gutted, I might have laughed. The day before, at a book store with some friends, I’d noticed a new book with Caroline’s name on it. I bought it without really even looking to see what it was. There aren’t a lot of author names I’ll jump at like that, but if Caroline wrote it, that’s enough for me.

Sure enough, Unspeakable tells about the sinking of the Empress of Ireland through the eyes of a fictional stewardess. Sigh. At least I get to look forward to reading it. And maybe someday there will be room for another story.

Sure enough, Unspeakable tells about the sinking of the Empress of Ireland through the eyes of a fictional stewardess. Sigh. At least I get to look forward to reading it. And maybe someday there will be room for another story.

As the tour wrapped up, I learned what I had suspected — the tour guide was Dr. John Willis, the Curator of the exhibit. The man who had done most of the historical research. The one training the volunteer tour guides who would take other people through the exhibit. The one who knew EVERYTHING about what they had included or not included, who knew the conscious decisions that had been made in putting together this display so that people wouldn’t just learn about the events, they’d feel them.

It was fascinating to learn about the Empress of Ireland and her passengers and crew, but no less so to learn about how an exhibit is put together — how you build a story with sound and space and pictures so that people can walk through it.

I’m glad I got lost in the right place, at the right time. Lucky, indeed. Thank you, Dr. John Willis and volunteer tour guides, for not kicking me out of your fascinating training session. And thank you to everyone who took the time to put this incredible exhibit together. I went through again on my own, later that same day, and took the time to read all the captions and listen to all the witness accounts and audio recordings. It was no less moving the second time through.

The display will be at the museum until April 2015; I think it moves to Halifax after that.

It’s worth a visit. Or two.